UK’s Brexit Woes Threaten Another Flagship Policy: Levelling-Up

Dashed hopes, so far at least, that Brexit would tilt Britain’s economy towards growth driven by trade and investment are threatening another of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s flagship policies: “levelling up” the regions outside of London.

Six years on from the vote to leave the European Union, the classic low-productivity British model of growth driven by consumption, supported in part by rising house prices, looks as strong as ever.

Britain has missed out on much of the global recovery in goods exports as economies re-opened from COVID-19 lockdowns, leaving it bottom among Group of Seven rich industrialised nations by this measure over the last 12 months.

The Resolution Foundation think tank this week said that lacklustre performance reflects a more closed economy since Brexit.

It also represents a missed opportunity for Johnson’s levelling-up agenda, which aims to reduce regional inequalities.

Had British goods exports grown in line with the average among the other six countries in the G7, they would have been worth around 38 billion pounds ($47 billion) more during the year to April 2022, based on a simple extrapolation.

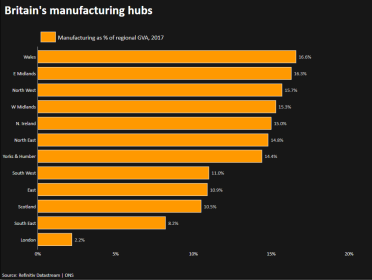

This represents several billions of pounds of lost revenue for British factories and by extension the regions outside of London, since around 95% of manufacturing output takes place outside the capital, according to 2017 official data.

Manufacturing comprises only about 10% of British economic output overall.

But it is a key driver of growth and investment in many of the parts of England and Wales that voted heavily to leave the EU in 2016, such as the East Midlands and North East regions.

Unless Britain can meaningfully improve its trade performance, it could mean more missed opportunities to level up.

“The regions that probably asked for Brexit are the most likely to have seen the biggest impact negative impact from trade,” said Flaheen Khan, senior economist from the Make UK manufacturing trade group.

On Wednesday the Resolution Foundation said Brexit was unlikely to result in a big restructuring of the main sectors of Britain’s economy – but it would have consequences for levelling-up.

“Our assessment finds that the North East, one of the poorest regions in the UK, will be one of the hardest hit, and that Brexit will increase its existing – and large – productivity and income gaps,” the think tank said.

Estimates of regional economic growth hint at the scale of the opportunity already lost.

In the first quarter of 2022, London’s economy – dominated by services firms – was 2.6% larger than its level of late 2019, before the onset of COVID-19.

By comparison, no other regional economy in the United Kingdom except for Northern Ireland had fully recovered its pre-pandemic size.

GETTING ON WITH IT

Proponents of Brexit say it is a long-term project that cannot be judged over the space of a few years, before the benefits of an independent trade and regulatory policy become fully apparent.

“Regurgitations of Project Fear don’t seem to get anyone anywhere,” said Britain’s minister for Brexit opportunities, Jacob Rees-Mogg, of this week’s Resolution Foundation report.

Britain’s government wants to boost exports of goods and services to reach 1 trillion pounds per year in current prices by the end of the decade, up from their pre-pandemic level of 700 billion pounds.

The highest rate of inflation in the G7 is likely to be a big driver behind meeting that goal but an improved underlying trade performance would go a long way to boosting economic activity across the United Kingdom.

Businesses, however, need more help to get there, the British Chambers of Commerce said.

It pointed to five practical measures that would boost trade with the EU which accounts for more than 40% of British exports, ranging from less red tape for food exports and a sales tax deal for small businesses trading digitally with the EU to arrangements for markings and testing of industrial goods.

“Businesses in the UK and EU still have good relationships and trust each other. We need decision-makers to follow our lead and negotiate practical improvements to the Brexit trade deal,” said William Bain, head of trade policy at the BCC.

Khan from Make UK said part of the problem for policymakers was that manufacturers had different needs in different parts of the country, with companies in the south of England seeking more spending on digital infrastructure, while those in the north were demanding better transport links.

One thing that is shared across the country is an acceptance that Brexit is now an economic reality, for better or worse.

“In an ideal world, trade would be frictionless, but they’ve accepted that’s not going to happen and most businesses, despite the impact, are getting on with it,” Khan said.

($1 = 0.8148 pounds)

(Reporting by Andy Bruce; Editing by Toby Chopra)