RAG Rage: Tales Of A Muddled Metaphor

Project organisations love traffic lights. There is something almost hypnotic about the red, amber, and green that draws management to this no-nonsense metaphor as a way of discriminating between the good, the bad and the ugly going on in a project.

For those who regard it as a chore to craft, finesse, interpret, extrapolate, and interpolate words, the iconic coloured box is a miracle of straight-talking messaging.

Accordingly, most project professionals have seen RAG statuses summarising everything from risk profiles and project health to KPI’s and budgetary rectitude.

I once applied the 3-colour coding to a product backlog to indicate which features would definitely be delivered, those that stood no chance and the rest that were touch and go.

Stakeholders who had signed up for Agile yet had become frustrated with my reluctance to guarantee the precise scope we would deliver, now showered me in compliments for the cogency of my multi-coloured statement of intent.

Though they couldn’t or wouldn’t listen to my finely nuanced words, they instinctively connected with the colours so peace prevailed until the next time their demands weren’t immediately met.

The problem is that simple techniques born of easily relatable analogies are only deceptively powerful.

Crude weapons don’t have safety catches or means of calibration and the same goes for traffic light tools whose simplicity makes them prone to misfire when they are called upon to convey the chunkier challenges of project work.

Given that even a brief survey of the history of traffic lights in the material world reveals no primordial logic to the system, it is hard to account for the impulsive way in which the metaphor is so often implemented.

An enlightening history

The first street traffic lights borrowed their palette from British railroads which had commonly used red, green, blue, black, and white flags, semaphores and lamps for signalling.

In January 1841, faced with a Parliamentary investigation into multiple accidents, the big players met to discuss safety.

Henry Booth of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway made the case for standardized hand signals and colour schemes: red for danger, white for safety and green to indicate “proceed with caution.”

By contrast, in the early days of the automobile in the US, many stop signs were yellow rather than red because at night it was all but impossible to see a red stop sign in a poorly lit area.

Detroit traffic officer William Potts created a three-color traffic signal in 1920, building on predecessors which had incorporated only red and green lights. The addition of an amber light for “caution” made driving safer and the three-color signal became the standard in the US by the mid-1930s.

Even today, the meaning of a red light at a traffic intersection varies according to context and country as demonstrated by the many turn right on red rules in right hand driving territories, including Germany where, during unification, the issue turned hot. And as for Japan’s notorious ‘blue’ Go lights, best not to go there!

The point is that traffic lights, like their metaphorical counterparts, mean what they are defined to mean. Red doesn’t always mean STOP and amber is as likely to mean stop unless it’s unsafe to do so as proceed with caution. In fact, in both China and Thailand, amber lights are interpreted so variably by road users that they have been replaced by countdowns.

So why is it that in the project world, we automatically assume RAG statuses have a universal – some might say oven-ready – meaning and commonly apply them with little formality or explanation?

Metaphor mishaps

Some organisations implicitly acknowledge the limitations of a simple RAG scheme through their adoption of a 4th, yellow status to carry the burden of some subtle distinction between green and amber perceived by their diligent PMO’s.

On several occasions, I have found myself arguing that red should be used sparingly and only when a project cannot proceed without a radical replan or injection of resources, after which the project should return to green.

Sadly, business interests weary of project teams letting them down often take the view that failure is eternal and that former failed projects should be permanently draped in the colour of anger, thereby denying the metaphor its ability to provide an early warning system during the rest of the project’s lifetime.

To limit the scope for misunderstanding and improve the precision of the messaging, I once spent a few hours supplementing a status report I had designed from scratch with at least 4 groups of RAG definitions aligned to different aspects of the project such as budget, quality, timelines etc.

The linguistic pedantry required was a salutary reminder that RAG statuses used carelessly were more likely to shroud in shadow and incite over-reaction than to shed light and instigate timely corrective action.

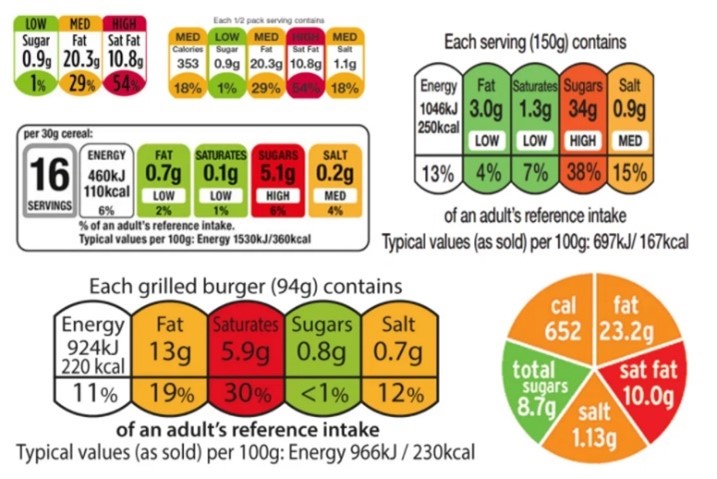

In the public sphere, traffic light systems have become a familiar feature. Take for instance, the most prevalent food-labelling scheme in the UK, tasked to encourage healthy eating and informed dietary choices.

Whilst most would agree the approach is helpful, too little consistency of presentation implementation and too many opportunities to sugar-coat negative data means that experts consider the scheme misleading, not fit for purpose and in urgent need of a rethink.

Travel Travails

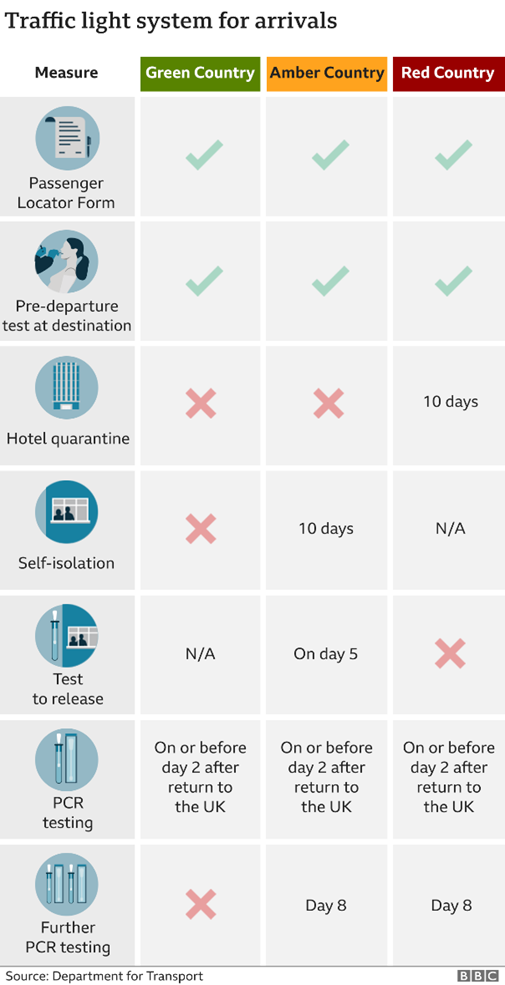

Which brings us to a highly topical and increasingly discredited adoption of a traffic light scheme that serves as a cautionary tale for rushed implementations of RAGs, namely the UK tool regulating international travel.

When proposed back in March, like all traffic light schemes, it had the ring of self-evident wisdom and easy practicality about it.

Looking ahead to May 17th, the target for lifting the ban on foreign travel, here was a logically structured system based on traffic life categorisation that would ease the country back to normality in a controlled and pragmatic way. What was not to like?

When, mid-May, the list of Green countries was released against increasing concern over the so-called Indian variant, the inherent weaknesses of the scheme from a Covid containment point of view became all too apparent.

But project managers up and down the country will have also been struck by something all too familiar: RAGs used opportunistically, inconsistently and ineffectually. In other words, for impact rather than merit.

RAG schemes tend to mash-up summary metrics, early warnings and triggers: if a milestone is green, progress is according to plan and no intervention is needed; if risk magnitude is amber, it has exceeded tolerances, requiring some kind of remediation; If a project is red, it is failing or failed and so needs to be recovered or shut-down.

The first flaw to call out with HMG’s RAGs is that all outbound travel is unconstrained and uncontrolled which most would call a green light.

However, given that most countries are designated amber or red, there is dissonance verging on paradox, made all the more contradictory still when ministers then say no one should travel, except in extremis.

In actual fact, the travel traffic light system is explicitly designed to serve only the return leg of a journey, but even here its application doesn’t seem well-served by everyone’s favourite metaphor.

The actions prescribed for return from Green countries do not signify an all-clear, a green flag, a green channel or a course of action that can proceed without risk.

Surely green countries should be those you can travel to and from without checks or risks. The fact that PCR tests are mandated for Green-listed countries infers intervention and risk which, by convention, is characterised by amber, not green.

Returns from red countries entail just one different measure from those from amber countries, namely hotel quarantine. It seems that only the inference of danger justifies use of a red traffic light as its primary connotation as an instruction to STOP is entirely absent from this usage.

The fact that travel to all countries is being discouraged but not prohibited and return from all countries comes with varying degrees of risk and associated mitigations suggests all countries should be listed as amber, though a wit might argue that some are more amber than others.

One can only concluded that this is as flawed an implementation of a traffic light metaphor as it’s possible to imagine: the public sent mixed signals, holiday companies accused of reckless profiteering, conflicted travellers, and responsible behaviour left to personal discretion; every one a red flag signifying communication failures of pandemic prevention policy!

Traffic Lights on Trial

The lessons from this bodged conscription of a very popular and valuable visual tool are, first and foremost that the Government continues to have a partial and cack-handed grasp of project management techniques and should think twice before borrowing from a discipline it doesn’t understand.

Outside government, the takeaway for architects of project frameworks is clearly to proceed with caution before green-lighting RAG schemes.

So seductive is this particular metaphor that it will rarely be resisted, but neglect to provide an underpinning of definitions and principles and such schemes soon fall into disrepute.

As their inadequacies are exposed and workarounds such as reporting green by default emerge it is only a matter of time before an audit blames them for failing to flag an impending project disaster and like one of the early street prototypes, the traffic lights will blow up in everyone’s face!

Boris, you have been warned!

Paul Holmes is an Agile PM/PRINCE2/MSP-Certified IT Programme Manager with a track record of delivering complex IT software projects.