How Senior Project Stakeholders Can Learn From The UKs’ Covid-19 Recovery Roadmap And Grow To Love Meta-Plans

Maybe due to jab-induced euphoria, but I surprised myself by how impressed I was by Boris Johnson’s 4-step Roadmap (to ease restrictions across England and provide a route back to a more normal way of life) which, for convenience, I will simply refer to it as the “Recovery Roadmap”.

Of course, the PM no more wrote the Roadmap than King James translated his eponymous bible but whoever are the real authors, it is very clear that after three lockdowns and 125,000 Coronavirus deaths, Boris managed to control his notorious ‘boosterism’ and pathological need to be popular (incidentally, a fatal flaw in any project manager) and finally listened to professionals whose preoccupations are not hugs and holidays but risk-based planning principles.

Believing that the number one reason for project failure is the behaviour of Stakeholders, my argument is that many of the customers, sponsors and stakeholders that we encounter in the project world could learn a lot from this fine example of a ‘meta plan’.

Format Wars and The Myth of Project Planning Predictability

Ever since the advent of Agile, the traditional Gantt chart project plan has found its raison d’être, value and format challenged.

Fifteen years ago, it would not have been unusual for Scrum evangelists to assert that in a world of Backlogs and Sprints, there was no place for a Microsoft project plan.

This was, of course, an over-simplification that failed to take account of the inter-relationships of software development, infrastructure commissioning, business change and external dependencies, all of which needed to be identified, understood, documented, and managed.

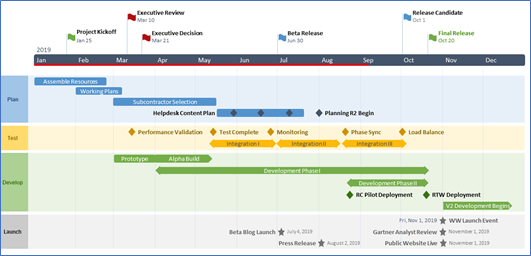

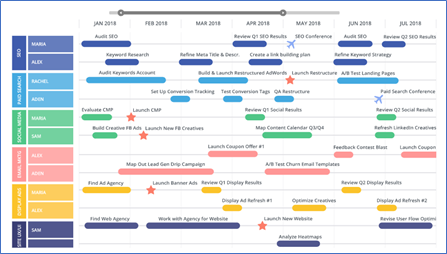

Partly due to the legacy of this dogma as well as the pressure from stakeholders to render complexity into a business-friendly set of “stars and bars” on a single presentation slide, it is now quite commonplace to inherit projects and even programmes which are planned only in PowerPoint or Excel spreadsheets, like these fine examples of the artform:

However, a “Plan on a Page” (POAP) is as blunt an instrument to manage a project as a sundial is to time a race so experienced hands know that these cartoonish project representations should always be heavily caveated and used sparingly as their separation from the context of underlying risks and issues means they can cynically be used up the stakeholder management chain to tell a vastly different story from that intended by the author.

Thus, the portrayal of a best-case scenario which allows for the possibility of slippage can be represented as a worst-case scenario, with the promise of even earlier delivery dates which the project team know are not achievable.

That said, Gantt charts are indigestible fare for those not tutored in the dark arts of planning, who need to quickly distil information to do their jobs. And whilst I am no cheerleader for Technicolor POAP’s, I acknowledge the paradox that more detail does not inevitably mean more accuracy.

Plans, however thorough and skilfully crafted are only snapshots of an informed guess at a moment in time.

Which is why seasoned project managers recognise that the best plans are not those that capture and scale every task and meticulously detail every dependency but those that are calibrated according to prevailing optimism/pessimism and/or incorporate contingency commensurate with the degree of uncertainty and negotiable urgency.

The observant will realise the brutal subtext of all this is that a ‘good’ plan is really a plan that gives me as a project professional, a sporting chance of hitting important milestones or basking in the fleeting glory of over-delivery when judged against a deliberately under-cooked set of delivery promises.

The problem is that senior stakeholders want and need certainty, whether that is the date when new capabilities will be ready for launch and monetisation or the knowledge that the project will complete in the right financial year for them to secure their bonuses.

But project managers are not oracles and project planning is too often a game of smoke and mirrors played with customers who cannot or will not tolerate the uncertainty that is intrinsic to any complex endeavour.

Meta-plans – the art of formalising uncertainty

So, you may ask, what does this commentary on the lot of project professionals have to do with the UK’s Pandemic Recovery Roadmap? My view is that, if regarded as belonging to a category of plan which has a unique purpose, it showcases when and how a meta-plan can unite the need for certainty with an inherently fluid set of variables that are otherwise impossible to capture in a conventional Gantt chart.

In a recent contract, I arrived as the 3rd programme manager in nearly 3 years to take control of a programme that was broken in every conceivable way. The plan I inherited looked plausible but under the covers was incomplete, poorly structured and produced dates which were built on sand.

Of course, I reported back my assessment to the board level stakeholders and the shareholders along with my proposal for a “Recovery Phase” to strengthen the programme with firmer foundations but the demands for a new “project plan” to be ready for the next sitting of the Steering Board were not pacified by rational arguments, primary amongst which was that a plan published prematurely was guaranteed to be worthless.

Unfortunately, confidence in the programme was already in shreds by the time I arrived on my white steed so my resistance won me only scepticism.

Fearing being set up as the fall guy for a complex web of risk and uncertainty that both internal and external stakeholders had neglected to recognise and mitigate over the preceding years of their oversight and fortified by Eisenhower’s dictum that “Plans Are Worthless, But Planning Is Everything”, I proposed a meta-plan which I promoted as “The Plan for a Plan”.

They didn’t like it (of course) but it was the only offer I was prepared to make in the circumstances and they accepted it grudgingly.

Importantly, it bought me just over 2 precious months in which to develop a meaningful plan founded on stable data, a comprehensive survey of the work remaining and informed by a deep appreciation of the risks and uncertainty that the programme would still be carrying after the Recovery Phase.

Happily, the majority of the intermediate milestones were met which meant that though I declined to share ongoing iterations of the Gantt I was building until the end of the process, I could still report meaningful progress to the shareholders.

The point here is that meta-plans are not just useful tools but, when project managers are confronted with a vast array of uncertainties, risks and variables, may be the only constructive way to plan. As such, they should therefore be valued as a valid planning method rather than treated as a ruse to postpone coming up with a “proper plan”.

Data not Dates

I am no fan of Boris’s slogans, whether “Build Back Better”, “Eat out to Help Out” or the all-time stinker, “Oven-ready deal” as they habitually over-simplify, are more sound-bite than sound policy and are cynically based on the assumption that if politicians use linguistic tricks like alliteration, a gullible public will swallow even the most fanciful nonsense.

However, the slogan “Data not Dates” which was used as the trailer for the Roadmap is none of those things and clearly came from a pm rather than the PM.

With the elegance of a Latin maxim, just those 3 words contain a chapter’s worth of project management wisdom and shall certainly be added to my arsenal of rhetoric. As slogan’s go, some might describe it as “world-beating” but best not to go there.

Plans are centred on dates whereas meta-plans are centred on the data on which key dates depend. The dates in meta-plans are therefore explicitly conditional and unapologetically fluid.

Meta-plans detail those events that are crucial to the planning process and therefore tend not to be concerned so much with tasks that culminate in an output (in the case of projects) or outcomes (in the case of programmes). The certainty provided by a meta-plan comes from the understanding it represents of the variables that need to be brought under control and rendered predictable.

Pugnacious stakeholders will proclaim that a meta-plan is “not good enough” and doesn’t give them the confidence or certainty they need to take the actions in their part of the business (such as sales, logistics or warehousing) to exploit the new products, services or capabilities and so this is rarely an easy sell.

However, where the scale of uncertainty (which in my case was a combination of known unknowns and unknown unknowns) means that most key dates have widely spaced pessimistic and optimistic values, the only alternative is advanced modelling which is way beyond the capabilities of Microsoft Project and most project professionals.

Meta-plans are therefore a very good option and Senior Stakeholders presented with such an offer would be wise not to dismiss them out of hand.

Boris’s Recovery Roadmap

Following the imposition of the 3rd lockdown shortly after Christmas, Tory backbenchers had been increasingly vociferous in their demand for fixed dates when the lockdown and related controls would be lifted along with a target to remove all Covid restrictions by the start of May.

Project professionals will be all too familiar with similar demands from powerful project stakeholders for whom the structured uncertainty of a meta-plan runs counter to their mindset.

It is easy to portray project managers’ caution as complacency and difficult for the project to prove that fixed dates cannot be set. Which is why I believe the UK Government deserves some credit for its response to these political demands which were echoed by most business interest groups.

Ahead of the launch of the Roadmap, there appeared to be a co-ordinated attempt to soften opposition forces with a barrage of guiding principles, including the “Data not Dates” slogan, the commitment to irreversibility in the removal of controls and a 4 step review process.

These are all good principles underpinning a credible meta-plan and releasing the principles ahead of the Roadmap itself meant that their obvious merits could be assimilated without the distraction of “no earlier than” dates that were bound to provoke an emotional and therefore irrational response.

When the roadmap was published on 22nd February 2021, 60 pages of detailed explanation were summarised by the Government in a familiar format:

The reaction was a combination of resignation and melodramatic disappointment, something seasoned PM’s are all too familiar with when trying to save senior stakeholders from their own gung-ho instincts.

However, no one was able to fault the approach and pre-empting the nit-picking over the “no earlier than….” dates, the Government also published its modelling to underpin a by-now familiar principle, namely that the Pandemic response would be guided by the science.

Quo Vadis? A return to Normal or destination Normal 2.0?

Yet despite all the good work that went into this Roadmap, there is a very big but because a roadmap to an unfamiliar destination is as good as a journey into the unknown.

Unfortunately, the intense political and business focus on lifting the lockdown and opening up the economy has seriously derailed efforts to understand where the Roadmap will take us.

Business just wants to ‘get back to normal’ whilst individuals are, if the tabloids are to be believed, fixated on foreign holidays and festivals. There is growing awareness that things will never be quite the same and as the only human virus that has ever been eradicated is smallpox, that Covid-19 will never not be with us.

However, there is no coherent national debate about Normal 2.0. This is typified by the Government’s vacillation around so-called Vaccine Passports (or Certificates) and the noisy heckling of libertarians who would rather lob the grenades of “discrimination” and “privacy” at those who dare to imagine different than sit down with them and model the new world that is just months away.

In the words of William Blake, we “must create a system or be enslaved by another mans” because countries, companies and the EU itself are already making decisions which will not be shaped by the UK’s cultural sensibilities.

And this is why the next big programme deliverable needed from the Government is, to use the language of MSP, a Blueprint for the future: the to-be processes for mass travel, cultural events and periodic vaccination; the new capabilities society needs to function; and what Business as Usual means for all sections of society and the economy.

If we don’t do this now, there is a danger of serious structural damage to our society and even, as some have speculated, Covid-19 becoming a disease of the poor, a truly disturbing prospect.

So far, the most the Government has done is to task Michael Gove with leading a review of the issues concerning vaccine passports but no matter how many experts are involved, modelling Normal 2.0, prototyping solutions and preparing the public for fundamental change to its privileges is what is needed.

In the project world, we would call the missing workstream “Business Change” and if it is not commissioned, however good the Recovery Roadmap, the long tail of Covid will not just be felt in terms of health but also in disruption to international travel and trade, social tensions, missed opportunities and a further deterioration in the public’s faith in Government, which is already at an all-time low.

The Recovery Roadmap marks a turning point in the Government’s willingness to learn from and adopt the disciplines of Project Management. But a return to a reactive, wait and see, tactical approach to the new world that is already taking shape around us will, ultimately, undo all the good work and jeopardize the restitution of the lives those of us fortunate to survive the pandemic, so crave.

Paul Holmes is an Agile PM/PRINCE2/MSP-Certified IT Programme Manager with a track record of delivering complex IT software projects.