True understanding of your team is not merely about knowing who they are, but also why they act as they do, and how their actions serve the collective goals of the group.

Whether these individuals report directly to you or have been brought together for educational purposes, the emotional intelligence of the leader is one of several success factors as a determinant of the team’s overall performance (Mayer et al., 2004).

Behavioral Diversity and Learning Engagement

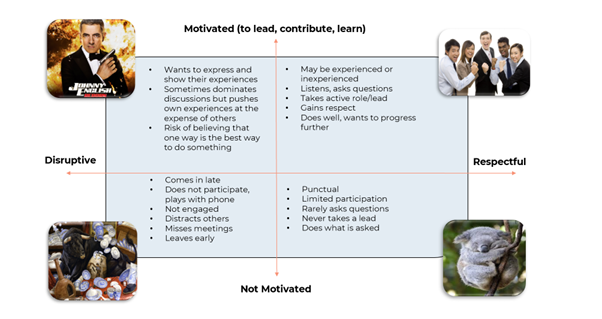

Participant behavior in teams varies significantly, as shown in Figure 1. The figure is a competing values framework with two axes: individuals who are motivated or not motivated and respectful or disruptive.

Figure 1: Competing values – attributes of individual behavior

There are disruptive yet driven individuals, like a bull in a china shop, who can derail initiatives if not properly guided. Then there are highly motivated but potentially disruptive individuals, like Johnny English, whose enthusiasm needs to be channeled toward productive ends.

On the quieter side, some team members resemble koalas, doing only what’s necessary and rarely taking initiative. They are dependable and do contribute but not motivated to go beyond the minimum.

The most beneficial to the team are those who actively contribute and lead (top right in Figure 1) — key players essential for driving success. Recognizing and managing these varied behaviors is crucial for building a successful team culture (Belbin, 2010). If understood and directed effectively, this spectrum of behaviors can be the difference between a team that merely functions and one that thrives.

Aligning Motivation with Bloom’s Taxonomy

The motivation to learn is a powerful driver that aligns closely with Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning. Motivated people tend to progress beyond mere knowledge acquisition, reaching toward the higher-order thinking skills of analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). These people are the ones who actively engage in discussions, ask probing questions, and take on leadership roles within the team and, on courses, lead the exercises and case studies.

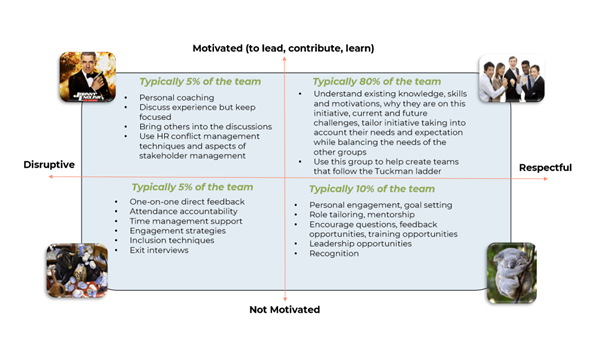

Figure 2: Competing values – response to individual behavior

Addressing Cognitive Biases and Emotional Journeys

However, it’s important to recognize a phenomenon like the Dunning-Kruger effect, where individuals with limited knowledge in a domain may overestimate their competence (Kruger & Dunning, 1999).

This effect can lead to challenges within the team, particularly when these individuals are motivated yet lack awareness of their limitations. If these people put themselves into leadership positions or are placed in leadership roles, the outcomes are predictable.

Conversely, the Kubler-Ross Change Curve, often used to describe grief stages, also applies to the learning process. Team members may initially experience denial or frustration before gradually accepting and integrating new knowledge and skills (Kübler-Ross, 1969).

Team leaders need to guide members through these emotional stages of learning and development. We also see this in projects where team members have oversold their capabilities. Under pressure, their behavior may change, and they might deflect blame onto others, which can be detrimental to the project.

In AIPMO’s experience with certification courses, participants have positioned themselves as experts or thought leaders yet struggle to lead or engage effectively during discussions or case studies.

These practical, transparent case studies are instrumental for assessment and contribute to exam scores. Such individuals may focus on peripheral aspects of the case studies, perform sub-optimally on exams, or, in more extreme cases, withdraw from the course altogether.

Strategically Supporting the Learning Continuum

To effectively support this diverse array of learning behaviors, one must employ tailored strategies. Personal coaching and targeted feedback can help motivate both the disruptively energetic and the quietly disengaged, aligning them with the team’s goals.

Conclusion: Cultivating Cohesion and Expertise

Understanding and decoding team behavior is an art form that calls for nuanced leadership. It’s about more than just managing; it’s about guiding a group of varied individuals toward a unified vision of success.

Such leadership is not merely transactional but transformational, requiring one to acknowledge and engage with each individual’s journey through the learning process.

In the broader narrative of team success, each member’s motivation, coupled with their position on Bloom’s taxonomy and their experience through the Kubler-Ross curve, plays an important role. As leaders, it’s our mandate to not only recognize these elements but to harmonize them in pursuit of collective excellence.

References

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological inquiry, 15(3), 197–215.

Belbin, R. M. (2010). Team roles at work. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Macmillan.

Article by Association of International Project Management Officers (AIPMO®).