Bank Of England’s Recession Warning Turns Spotlight To UK Budget Plan

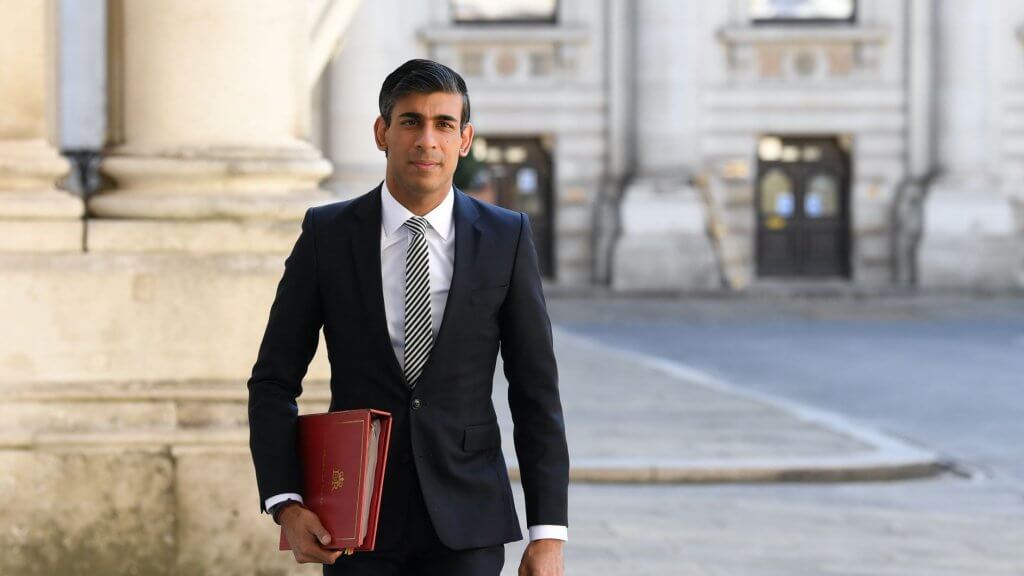

The risk of a two-year recession in Britain, flagged this week by the Bank of England, underscores the high stakes for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and his finance minister Jeremy Hunt as they prepare to announce major tax increases and spending cuts.

The BoE said on Thursday that Britain’s economy would shrink for eight three-month quarters in a row – the longest such run in at least a century – if interest rates go up by as much as financial markets have been expecting recently.

That would be a longer and shallower economic contraction than the ones that followed the COVID-19 lockdowns and the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

But the backdrop of high inflation this time is limiting the policy options available to the government.

Even if borrowing costs do not rise any further at all, the BoE’s forecasts still paint a grim picture of an economy contracting in five of the next six quarters under the strain of a tight cost-of-living squeeze.

Officials from the central bank stress that their mission is to bring down inflation which is currently running above 10%, more than five times their 2% target, and that economic pain in the short-term will be needed to achieve that.

“Our target is ultimately not on the real economy. Our target necessarily, because we’re running monetary policy, is to contain inflation,” BoE Chief Economist Huw Pill said in an interview with CNBC television on Friday.

“(The) slowdown in the economy is what we anticipate is required to contain domestic inflationary pressures to achieve our targets,” he added.

Against that backdrop, Sunak and Hunt must deliver a plan to repair the public finances that not only reassures investors who took fright at former prime minister Liz Truss’s unfunded tax cut plans but which also limits the hit to the economy.

Sterling fell to a record low against the U.S. dollar in the wake of Truss’s mini-budget and the Bank of England had to step in and buy 19 billion pounds of government bonds to halt a firesale of assets by British pension funds.

Hunt has warned of tough decisions on taxes and spending as he prepares to announce the new government’s first budget programme on Nov. 17.

Jagjit Chadha, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, a think-tank, said typical recession responses would not work given that the main problem in Britain, and in many other rich economies, was an inflationary energy price shock.

“This is not a recession we should be offsetting with lower interest rates and expansionary fiscal policy,” Chadha said. “That said we do need to be helping the poorest households who have been through some pretty torrid years.”

Media reports have suggested Hunt and Sunak might take that approach by looking at raising taxes on dividends and capital gains and extending a windfall tax on energy firms to help fill a 50 billion-pound hole in the public finances, although analysts also expect more tightening of public spending too.

Luke Bartholomew, senior economist at fund management firm abrdn, said the ruling Conservative Party had learned from its own experiments with austerity a decade ago that spending cuts cause more pain to the economy than tax increases.

But the real test for Sunak and Hunt and their ability to keep their own lawmakers supportive of their fiscal medicine would come next year, when an expected 2024 election will be on the horizon and the economy inevitably goes into recession.

The Conservatives have a lot of ground to catch up with voters. The opposition Labour Party had a 26-point lead over the Conservatives in a YouGov opinion poll conducted on Nov. 1-2, up from an 8-point lead on the eve of Truss’s mini-budget.

“There’s not much they can do” to avoid a recession, Bartholomew said. “The issue is to keep it as shallow as possible and come out of it by 2024 so they can be going into an election saying that we are in a recovery.”

(Additional reporting by David Milliken;Writing by William Schomberg; Editing by Jon Boyle)