Nuclear Fusion Backers Meet In US Capital As Competition With China Looms

Leaders in the emerging Western nuclear fusion industry are convening in Washington, D.C., this week seeking ways to attract more money for research to avoid falling far behind China in the race to develop and build commercially viable reactors.

A funding bill signed by President Joe Biden this month contained $790 million for fusion science programs for 2024, below the more than $1 billion backers say is needed.

Scientists, governments, and companies are racing to harness fusion, the nuclear reaction that powers the sun, to provide carbon-free electricity. It can be replicated on Earth with heat and pressure using lasers or magnets to fuse two light atoms into a denser one, releasing large amounts of energy. Unlike plants that run on fission, or splitting atoms, commercial fusion plants, if ever built, would not produce long-lasting radioactive waste.

Andrew Holland, CEO of Fusion Industry Association, or FIA, which is hosting a two-day conference, said a fear is that fusion will follow the pattern of the solar industry where much of the technology was invented in the U.S., but manufacturing came to be dominated by China.

“It is very clear that China has ambitions to do the same sort of thing, both in the supply chain and the developers,” Holland told Reuters. “It’s time for the U.S. to respond to that challenge.”

Private companies around the world have raised more than $6 billion through 2022, a FIA report said last July. The report mostly did not count private money going to fusion in China, which is harder to track.

Much more funding is needed to bring fusion from lab experiments to commercial enterprises, backers said.

“There’s no way we can get to where we need to go unless there’s funding coming from the government side and from the private sector side,” David Turk, the deputy U.S. energy secretary, told the conference.

FIA’s third annual conference is expected to attract about 350 attendees from countries including the U.S., UK, Germany and Japan, more than the roughly 100 attendees in previous years.

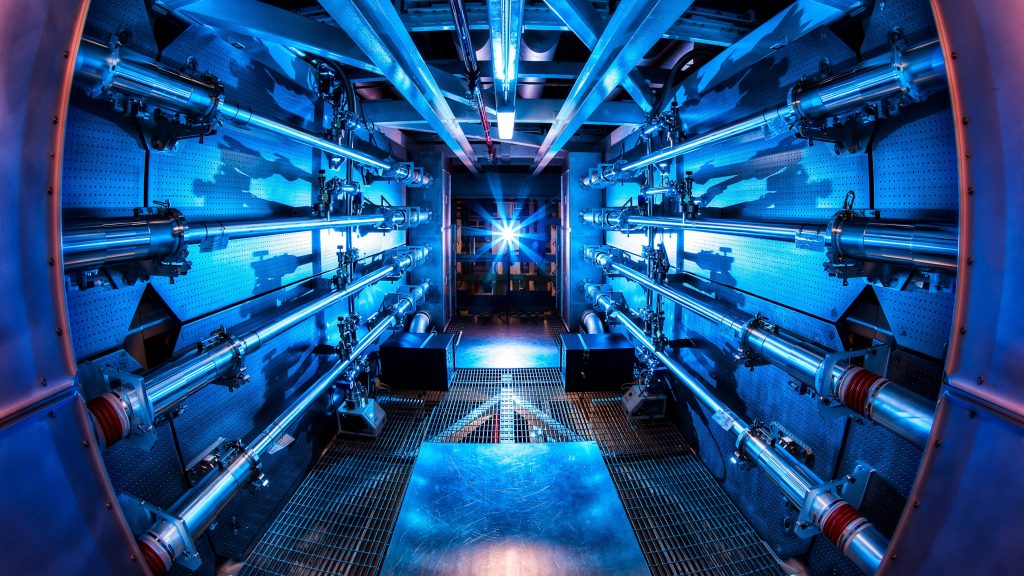

Fusion built momentum last year when scientists at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in California using lasers repeated a fusion breakthrough. Holland says fusion will be providing power to the grid in a decade.

Not everyone puts faith in that timeline. “Maybe he means dog years. Even that would be optimistic,” said Victor Gilinsky, a physicist and former Nuclear Regulatory Commission commissioner. Gilinsky estimates that the energy yielded from the lab reaction, which only lasted an instant, was about 1% of the energy used to fire up the lasers.

Still, Holland said funding fusion research should be a priority in the fight against climate change.

“Fusion should get significantly more and that wouldn’t take away from the deployment of much needed other clean energy technologies.”

(Reporting by Timothy Gardner; Editing by David Gregorio)